Strictly Personal

Africa’s ‘kill the gays’ laws may be good for its nation-building and economic recovery, By Charles Onyango-Obbo

Published

11 months agoon

Uganda President Yoweri Museveni, at the start of the week, signed into law the world’s harshest anti-LGBTIQA+ bill. Dubbed by critics the “Kill the Gays” law, it imposes the death penalty or life imprisonment for certain same-sex acts, up to 20 years in prison for “recruitment, promotion and funding” of same-sex “activities,” and the death penalty for “attempted aggravated homosexuality.”

Uganda joins just a handful of countries in the world penalising lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer/questioning, asexual (LGBTIQA+) people with death: Afghanistan, Brunei, Iran, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen, Mauritania, and Somalia.

A key force behind the “Kill the Gays” bill is conservative Ugandan cultural and Christian groups in alliance with American fundamentalist churches. Their success has been spectacular, because Uganda becomes the first majority “Christian country” that has a law that specifies hanging and life imprisonment for some homosexual acts.

The “Kill the Gays” law might be shocking in its cruelty, but it is made possible by the high levels of homophobia in the country. Some polls have put opposition to homosexuality at over 90 per cent. This is strange because, in Uganda, there is a near epidemic of rape and defilement of children by heterosexual men and virtually no attacks by homosexuals.

This tells us that, like in other countries like Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, where homophobia is on a new spike, this is not about the threat paused by homosexuality. It is, first and ironically, about the terror of what the cultural and political establishments view as heterosexual deviance.

It is expressed in homophobia, which they consider an even worse form of deviance because of more hate and widespread fear of it. Because of that, it is a significant and cheap bipartisan issue that governments facing risky legitimacy crises can’t resist tapping into. In fact, they need it.

This is bigger than Uganda. If one looks ahead, the news is not good – a decade of virulent homophobia and “kill the gays” laws is coming to Africa.

It is possible to see where that wave will be highest. It will be in countries failing to manage their debt and other economic crises and where elite factionalism is high — like Ghana, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and possibly Kenya. It will be mild or non-existent in countries not in debt peril (or where governments can pay it) or dire economic straits, including Botswana, Benin, Madagascar and Eswatini.

A big part of this homophobia is a response to a changing world and the fear by the old, cultural and political guardians of what they see ahead. These guardians rightly view sexual liberation and other new forms of expression as central to the new subversive order.

Not only are young Africans on a rampage of free sex that they post on their social media pages, but there are also many of them who are not doing it; they are abstaining, getting married late or not at all, or choosing single motherhood (African men today are unworthy, too many young women claim).

There is also a growing army of something the elders don’t understand; African men who don’t want to settle down or be fathers. Some of these young men have grandfathers who are still alive and grew up in a time when they thought it was their duty to make every young woman in their village or street pregnant, and where the only serious men were polygamists.

Their betrayal is too much.

As if that wasn’t enough, there has been an outbreak of what the traditionalists describe as “uncontrollable” and “ungovernable” African women all over the place. They bow to no man (choose which one they will date long-term or sleep with for a one-night stand), have their own money and careers, and dare go out in groups and buy their own drinks.

And many African women are bisexual.

Looking at all this, the guardians think the Devil is using homosexuality to bring the collective African nation down. Criminalising gay sex, to them, the most permissive form of social liberation and “Western cultural imperialism,” and shepherding the “lost sheep” back into the fold so they can produce more children to keep society strong — as their parents and grandparents did — is a strategic and national security imperative.

Therefore, the homophobic national consensus in many countries will be an important basis for nation-building and economic recovery on the continent for a while. It will get louder and nastier.

One could even argue that it would be concerning if “kill the gays” laws like Uganda’s didn’t come to pass. It would have suggested that there was no social transformation and disruption of the old world. Or at least not enough to worry the elders.

Uganda’s anti-gay war is part of a broader proxy war, over easily the most far-reaching social and cultural transformation in Africa of the post-independence era. Great wars are made great by the stories of their heroes, and world-changing causes need martyrs.

Ugandan prisons full of people who were jailed because they wore rainbow T-shirts or were consenting adult men who kissed each other on the cheeks in their living room but were seen by a nosy peeping Tom neighbour who reported them to the police might be the cast of heroes and martyrs it needs.

They could be the bricks with which a future free society beyond the suffocating one the ruling National Resistance Movement has imposed on it for nearly 40 years is built.

Charles Onyango-Obbo is a journalist, writer, and curator of the “Wall of Great Africans”. Twitter@cobbo3

You may like

-

Air Peace, capitalism and national interest, By Dakuku Peterside

-

Ghana’s VP Bawumia throws weight behind anti-LGBTQ campaign

-

This is chaos, not governance, and we must stop it, By Tee Ngugi

-

Off we go again with public shows, humbug and clowning, By Jenerali Uliwengu

-

How patriarchy underpins gender violence today, By Tee Ngugi

-

Help! There’s a dangerous, secret plot to save the EAC from imminent death, By Charles Onyango-Obbo

Strictly Personal

Air Peace, capitalism and national interest, By Dakuku Peterside

Published

1 week agoon

April 16, 2024

Nigerian corporate influence and that of the West continue to collide. The rationale is straightforward: whereas corporate activity in Europe and America is part of their larger local and foreign policy engagement, privately owned enterprises in Nigeria or commercial interests are not part of Nigeria’s foreign policy ecosystem, neither is there a strong culture of government support for privately owned enterprises’ expansion locally and internationally.

The relationship between Nigerian businesses and foreign policy is important to the national interest. When backing domestic Nigerian companies to compete on a worldwide scale, the government should see it as a lever to drive foreign policy, and national strategic interest, promote trade, enhance national security considerations, and minimize distortion in the domestic market as the foreign airlines were doing, boost GDP, create employment opportunities, and optimize corporate returns for the firms.

Admitted nations do not always interfere directly in their companies’ business and commercial dealings, and there are always exceptions. I can cite two areas of exception: military sales by companies because of their strategic implications and are, therefore, part of foreign and diplomatic policy and processes. The second is where the products or routes of a company have implications for foreign policy. Air Peace falls into the second category in the Lagos – London route.

Two events demonstrate an emerging trend that, if not checked, will disincentivize Nigerian firms from competing in the global marketplace. There are other notable examples, but I am using these two examples because they are very recent and ongoing, and they are typological representations of the need for Nigerian government backing and support for local companies that are playing in a very competitive international market dominated by big foreign companies whose governments are using all forms of foreign policies and diplomacy to support and sustain.

The first is Air Peace. It is the only Nigerian-owned aviation company playing globally and checkmating the dominance of foreign airlines. The most recent advance is the commencement of flights on the Lagos – London route. In Nigeria, foreign airlines are well-established and accustomed to a lack of rivalry, yet a free-market economy depends on the existence of competition. Nigeria has significantly larger airline profits per passenger than other comparable African nations. Insufficient competition has resulted in high ticket costs and poor service quality. It is precisely this jinx that Air Peace is attempting to break.

On March 30, 2024, Air Peace reciprocated the lopsided Bilateral Air Service Agreement, BASA, between Nigeria and the United Kingdom when the local airline began direct flight operations from Lagos to Gatwick Airport in London. This elicited several reactions from foreign airlines backed by their various sovereigns because of their strategic interest. A critical response is the commencement of a price war. Before the Air Peace entry, the price of international flight tickets on the Lagos-London route had soared to as much as N3.5 million for the economy ticket. However, after Air Peace introduced a return economy class ticket priced at N1.2 million, foreign carriers like British Airways, Virgin Atlantic, and Qatar Airways reduced their fares significantly to remain competitive.

In a price war, there is little the government can do. In an open-market competitive situation such as this, our government must not act in a manner that suggests it is antagonistic to foreign players and competitors. There must be an appearance of a level playing field. However, government owes Air Peace protection against foreign competitors backed by their home governments. This is in the overall interest of the Nigerian consumer of goods and services. Competition history in the airspace works where the Consumer Protection Authority in the host country is active. This is almost absent in Nigeria and it is a reason why foreign airlines have been arbitrary in pricing their tickets. Nigerian consumers are often at the mercy of these foreign firms who lack any vista of patriotism and are more inclined to protect the national interest of their governments and countries.

It would not be too much to expect Nigerian companies playing globally to benefit from the protection of the Nigerian government to limit influence peddling by foreign-owned companies. The success of Air Peace should enable a more competitive and sustainable market, allowing domestic players to grow their network and propel Nigeria to the forefront of international aviation.

The second is Proforce, a Nigerian-owned military hardware manufacturing firm active in Rwanda, Chad, Mali, Ghana, Niger, Burkina Faso, and South Sudan. Despite the growing capacity of Proforce in military hardware manufacturing, Nigeria entered two lopsided arrangements with two UAE firms to supply military equipment worth billions of dollars , respectively. Both deals are backed by the UAE government but executed by UAE firms.

These deals on a more extensive web are not unconnected with UAE’s national strategic interest. In pursuit of its strategic national interest, India is pushing Indian firms to supply military equipment to Nigeria. The Nigerian defence equipment market has seen weaker indigenous competitors driven out due to the combination of local manufacturers’ lack of competitive capacity and government patronage of Asian, European, and US firms in the defence equipment manufacturing sector. This is a misnomer and needs to be corrected.

Not only should our government be the primary customer of this firm if its products meet international standards, but it should also support and protect it from the harsh competitive realities of a challenging but strategic market directly linked to our national military procurement ecosystem. The ability to produce military hardware locally is significant to our defence strategy.

This firm and similar companies playing in this strategic defence area must be considered strategic and have a considerable place in Nigeria’s foreign policy calculations. Protecting Nigeria’s interests is the primary reason for our engagement in global diplomacy. The government must deliberately balance national interest with capacity and competence in military hardware purchases. It will not be too much to ask these foreign firms to partner with local companies so we can embed the technology transfer advantages.

Our government must create an environment that enables our local companies to compete globally and ply their trades in various countries. It should be part of the government’s overall economic, strategic growth agenda to identify areas or sectors in which Nigerian companies have a competitive advantage, especially in the sub-region and across Africa and support the companies in these sectors to advance and grow to dominate in the African region with a view to competing globally. Government support in the form of incentives such as competitive grants ,tax credit for consumers ,low-interest capital, patronage, G2G business, operational support, and diplomatic lobbying, amongst others, will alter the competitive landscape. Governments and key government agencies in the west retain the services of lobbying firms in pursuit of its strategic interest.

Nigerian firms’ competitiveness on a global scale can only be enhanced by the support of the Nigerian government. Foreign policy interests should be a key driver of Nigerian trade agreements. How does the Nigerian government support private companies to grow and compete globally? Is it intentionally mapping out growth areas and creating opportunities for Nigerian firms to maximize their potential? Is the government at the domestic level removing bottlenecks and impediments to private company growth, allowing a level playing field for these companies to compete with international companies?

Why is the government patronising foreign firms against local firms if their products are of similar value? Why are Nigerian consumers left to the hands of international companies in some sectors without the government actively supporting the growth of local firms to compete in those sectors? These questions merit honest answers. Nigerian national interest must be the driving factor for our foreign policies, which must cover the private sector, just as is the case with most developed countries. The new global capitalism is not a product of accident or chance; the government has choreographed and shaped it by using foreign policies to support and protect local firms competing globally. Nigeria must learn to do the same to build a strong economy with more jobs.

Strictly Personal

This is chaos, not governance, and we must stop it, By Tee Ngugi

Published

2 weeks agoon

April 10, 2024

The following are stories that have dominated mainstream media in recent times. Fake fertiliser and attempts by powerful politicians to kill the story. A nation of bribes, government ministries and corporations where the vice is so routine that it has the semblance of policy. Irregular spending of billions in Nairobi County.

Billions are spent in all countries on domestic and foreign travel. Grabbing of land belonging to state corporations, was a scam reminiscent of the Kanu era when even public toilets would be grabbed. Crisis in the health and education sectors.

Tribalism in hiring for state jobs. Return of construction in riparian lands and natural waterways. Relocation of major businesses because of high cost of power and heavy taxation. A tax regime that is so punitive, it squeezes life out of small businesses. Etc, ad nauseam.

To be fair, these stories of thievery, mismanagement, negligence, incompetence and greed have been present in all administrations since independence.

However, instead of the cynically-named “mama mboga” government reversing this gradual slide towards state failure, it is fuelling it.

Alternately, it’s campaigning for 2027 or gallivanting all over the world, evoking the legend of Emperor Nero playing the violin as Rome burned.

A government is run based on strict adherence to policies and laws. It appoints the most competent personnel, irrespective of tribe, to run efficient departments which have clear-cut goals.

It aligns education to its national vision. Its strategies to achieve food security should be driven by the best brains and guided by innovative policies. It enacts policies that attract investment and incentivize building of businesses. It treats any kind of thievery or negligence as sabotage.

Government is not a political party. Government officials should have nothing to do with political party matters. They should be so engaged in their government duties that they literally would not have time for party issues. Government jobs should not be used to reward girlfriends and cronies.

Government is exhausting work undertaken because of a passion to transform lives, not for the trappings of power. Government is not endless campaigning to win the next election. To his credit, Mwai Kibaki left party matters alone until he had to run for re-election.

We have corrupted the meaning of government. We have parliamentarians beholden to their tribes, not to ideas.

We have incompetent and corrupt judges. We have a civil service where you bribe to be served. Police take bribes to allow death traps on our roads. We have urban planners who plan nothing except how to line their pockets. We have regulatory agencies that regulate nothing, including the intake of their fat stomachs.

We have advisers who advise on which tenders should go to whom. There is no central organising ethos at the heart of government. There is no sense of national purpose. We have flurries of national activities, policies, legislation, appointments which don’t lead to meaningful growth. We just run on the same spot.

Tee Ngugi is a Nairobi-based political commentator

EDITOR’S PICK

Tanzania’s auto-tech startup Spana is simplifying car maintenance— CEO

Tanzania’s auto-tech startup, Spana, has developed a mobile application for a bouquet of automobile services, enabling individual car owners and...

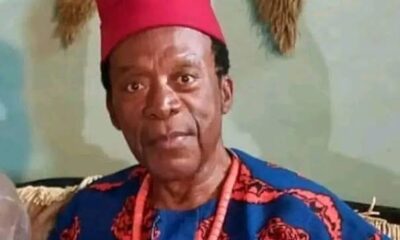

Nollywood thrown into mourning as another veteran actor Zulu Adigwe passes on

The Nigerian movie industry, popularly known as Nollywood, has once again been thrown into mourning with the death of veteran...

Zambian FA boss, Gen.Sec arrested over alleged laundering of K341,902

President of the Football Association of Zambia (FAZ), Andrew Kamanga, has been arrested along with the Secretary-General and two other...

Luapula businessman, Munsanje, reflects on media freedoms and freedom of expression

As stakeholder engagement intensifies regarding the ongoing project to amplify voices on media freedom, freedom of expression, and digital rights,...

World Bank stops tourism fund to Tanzania’s Ruaha park. Here’s why

A spokesperson for the World Bank said on Wednesday that the lender had stopped all new payments from a $150...

‘It would be risky to release Binance executive from custody risky’, Nigerian govt says

Nigeria’s anti-corruption agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), believes admitting the detained executive of cryptocurrency firm, Binance Holdings...

President de Sousa insists Portugal must ‘pay costs’ of slavery, colonial crimes

Following recent conversations around reparations to countries with colonial heritage, Portuguese President, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, has added his voice...

Nigeria’s antigraft agency EFCC may try 300 forex racketeers

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Nigeria’s anti-corruption body, could go after 300 forex criminals who trade on a...

Institute calls for responsible social media usage among youths

Smart Zambia Institute has reiterated the importance of youths to use social media responsibly. Senior Business Applications Officer at the...

Digital Rights: Policy enthusiast, Jere, advocates self-regulation as alternative to govt regulations

Copperbelt businessman and mining policy advocate, George Jere, has highlighted the importance of self-regulation in the expanding digital media landscape,...

Trending

-

Culture1 day ago

Culture1 day agoEgypt reclaims 3,400-year-old stolen statue of King Ramses II

-

Metro2 days ago

Metro2 days agoNigerian govt shuts Chinese supermarket over ‘no-Nigerian shopper’ allegation

-

Musings From Abroad13 hours ago

Musings From Abroad13 hours agoPresident de Sousa insists Portugal must ‘pay costs’ of slavery, colonial crimes

-

VenturesNow2 days ago

VenturesNow2 days agoNigeria wants $2.25 billion World Bank loan